Response of Workplaces in South Korea to the COVID-19 pandemic in the first 100 days

The majority of COVID-19 workplace group infections were observed in healthcare facilities, call centers, and public service offices. Responses to workplace COVID-19 infections primarily included workplace distancing, flexible working schedules, early identification of workers suspected to be infected, and disinfection.

100 Tage nach der Diagnose des ersten COVID-19-Falls entfielen in Südkorea 17,4 Prozent der bestätigten Fälle auf Gruppeninfektionen am Arbeitsplatz, einschließlich Gesundheitseinrichtungen, Call-Centern und in der öffentlichen Verwaltung. Die Reaktion in der Arbeitswelt erfolgte, nachdem Südkorea Alarmstufe Gelb für Infektionskrankheiten ausgerufen hatte. Das Land erließ Richtlinien, um das Risiko einer Ansteckung mit dem COVID-19-Erreger am Arbeitsplatz zu verringern. Diese Richtlinien enthielten unter anderem Maßnahmen zur Förderung des Abstandhaltens bei der Arbeit, zu flexiblen Arbeitszeiten, zur frühzeitigen Identifikation infektionsverdächtiger Beschäftigter und zur Desinfektion. In Vorbereitung auf erneute Ausbrüche der Pandemie oder das Auftreten eines neuen Erregers ist auch weiterhin eine Gefährdungsbeurteilung für jeden Arbeitsplatz notwendig, die den Infektionsschutz berücksichtigt. Langfristig sollte der Gesundheitsschutz bei der Arbeit als ein wichtiger Teil des nationalen Krisenreaktionssystems behandelt werden, sodass sofortige und widerspruchsfreie Maßnahmen umgesetzt werden können.

Aus Zeitgründen war eine Übersetzung des Beitrags ins Deutsche leider nicht möglich.

Outbreak of COVID-19 in society and the workplace

COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, is an unprecedented global public health crisis. South Korean workers have been confronted with various serious occupational health risks that were not yet fully understood by the policy-making authorities. This report presents the incidence trends of workplace COVID-19 infections and the responses to the infection in South Korea within 100 days of diagnosis of the first COVID-19 case in Korea. Since the above have not yet been comprehensively evaluated in workplaces, we assembled the daily announcements of the central and local governments[1] and analyzed the major cases of group infection in workplaces to visualize the overall trend of workplace infections.

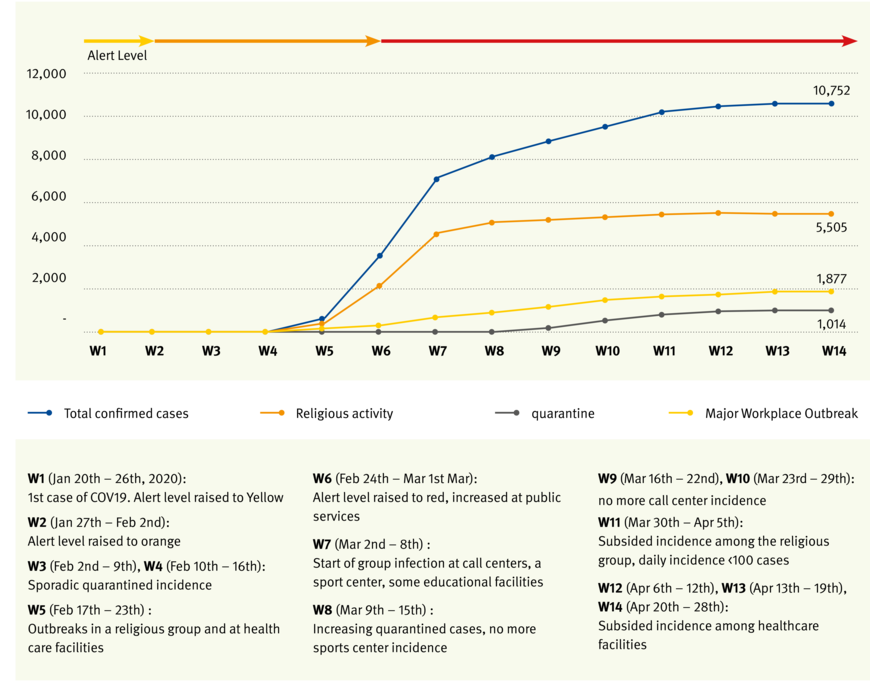

By April 28, 2020, 10.752 COVID-19 cases had been diagnosed through 608.514 tests, including 244 deaths, representing a 2.3 percent case fatality rate[2] [3]. Figure 1 presents the weekly incidence of confirmed cases by major group infection. The incidence of COVID-19 was sustained with the occurrence of sporadic, quarantined cases until the 3rd week of the first 100 days. It rapidly increased after identification of the super spreader case from a religious group, surging on February 29 (5th week). About 5 weeks later, with comprehensive PCR testing and nationwide Public-Private academic cooperation, the number of new cases dropped to under 100 (11th week)[4] [5].

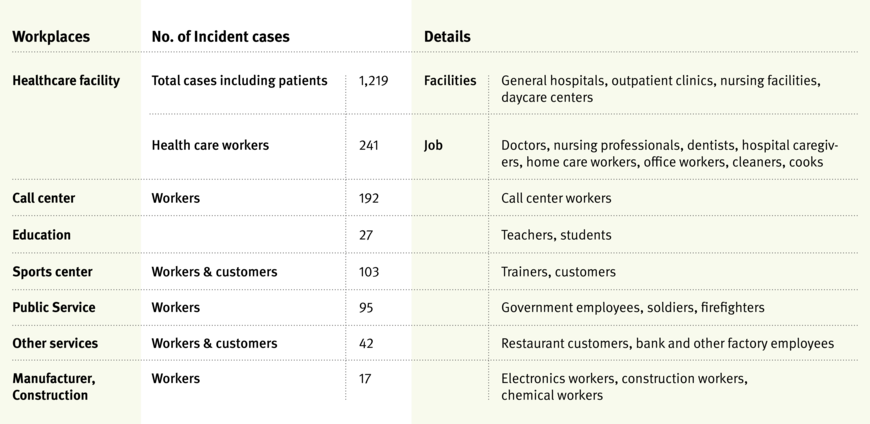

From among 10.752 COVID-19 cases, major group infections reported by central and local authorities belonged to religious groups (51.4 percent) and workplaces (17.4 percent). The incidence in workplaces started to increase along with that in religious groups by the end of the 5th week, when the COVID-19 alert level was raised to red (Grafik 1). Several types of workplaces reported group infections, including public service offices (6th week), call centers, sport centers, and educational facilities (7th week) (Grafik 1). The highest incidence was observed in health care facilities, followed by call centers, sports centers, and public service offices (Tabelle 1). The increased incidence was sustained for longer in health care facilities than in other workplaces (14th week), indicative of the high risk of direct contamination faced by workers at these facilities during patient care. As of April 5, 2020, the KCDC reported that 2.4 percent of confirmed COVID-19 cases were health care workers, and 1.0 percent was infected in a work-related environment[6].

Incidence among call center workers continued to increase for four weeks (11th week) (Grafik 1). Most of the cases in call centers were among workers situated in a high-density work environment. A recent report from a call center outbreak in Seoul revealed that 92 (8 percent of the total workers) were diagnosed with COVID-19, representing an attack rate of 43.5 percent. This showed that crowded office settings such as call centers could be exceptionally contagious sources of further transmission[7].

Participants in a leadership seminar held in a local sports center during the 6th week became spreaders in several other local sports centers. Physical activity and close kinship during the seminar rendered them highly contagious. Most of the group infection cases were customers infected by their sports teachers.

The work burden of public service officers increased greatly during the emergency response period, resulting in exhaustion. This group included workers in health departments and prisons, firefighters, and police officers. Although the infection route among them is not yet clear, the importance of public service officers in emergency response needs to be emphasized.

Not many group infections were reported from manufacturing industries, possibly due to the presence of younger, asymptomatic cases.

Response to COVID-19 in society and workplaces

The basic acts formulated for emergency response in South Korea are:

- Framework Act on the Management of Disasters (FAMD), and

- Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act (IDPA).

According to (1), the government can initiate the response system to control national disasters, including pandemics, and the regulation-related act (2) relates the action specifically to infection control.

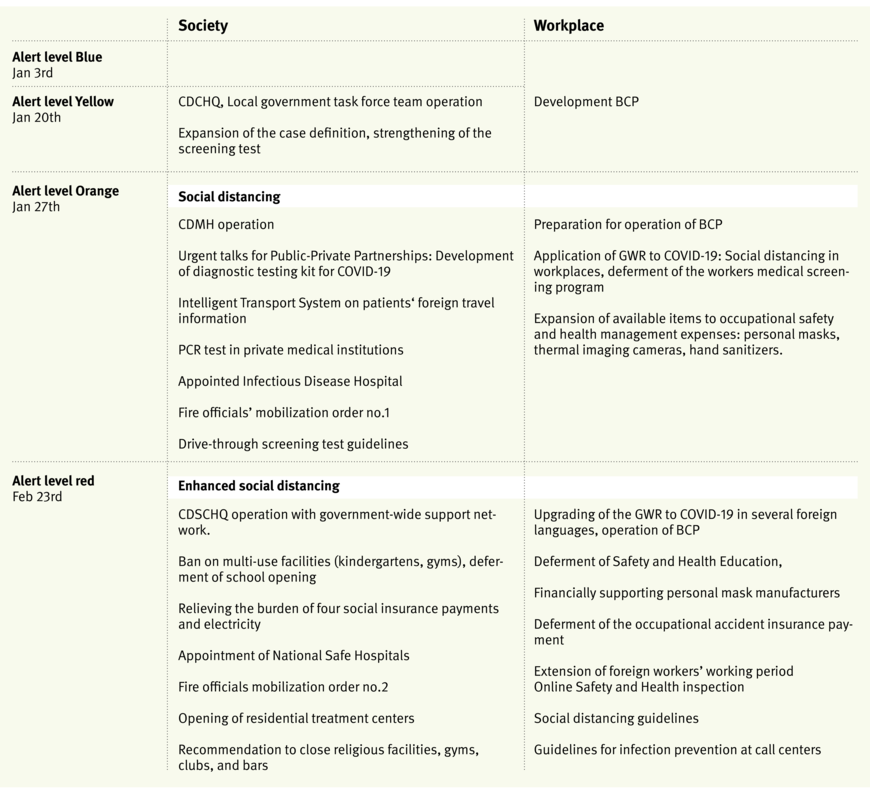

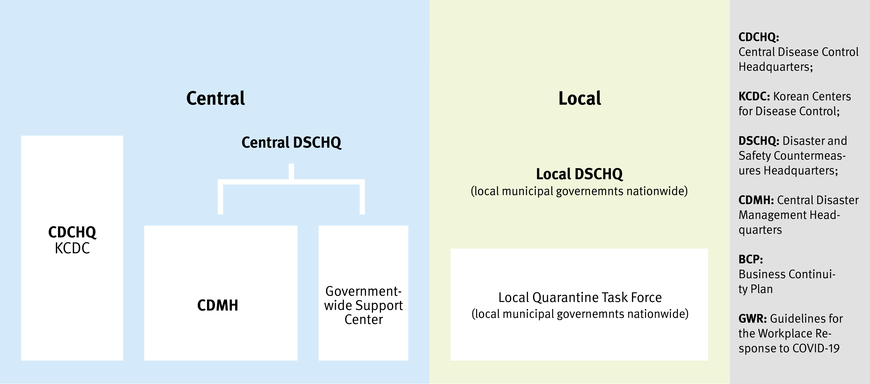

Based on FAMD, the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) developed the Infectious Disease Crisis Management Standard Manual. According to this manual, KCDC raised the alert level for infectious disease to blue considering the pneumonia cases in China. On January 20, the KCDC announced the occurrence of the first COVID-19 case in South Korea, raised the alert level to yellow, and began operations in the Central Disease Control Headquarters (CDCHQ). The Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Energy recommended formulating a Business Continuity Plan (BCP) during alert levels blue and yellow (Tabelle 2).

After raising the alert level to orange (Jan 27, 2020), the Central Disaster Management Headquarters (CDMH) started to operate with government-wide support systems. The CDMH prepared to fast-track the development of COVID-19 diagnostic testing kits by holding urgent Private-Public Partnership talks. They provided doctors with access to the travel information of patients through the Intelligent Transport System (ITS), increased the number of screening stations and infectious disease hospitals, and distributed the drive-through screening test guidelines. Most of those policies were based on the FAMD and IDPA.

Workplace policy was also determined by the CDMH and ministry of employment and labor. The major policy for workplaces was presented in the ”Guidelines for the Workplace Response (GWR) to COVID-19 infection”.

The important contents of the GWR include:

- Strengthening of worker hygiene management and maintain cleanliness and disinfection at workplaces,

- Prevention of infection and spread in the workplace,

- Establishment of a protocol to detect suspected or confirmed patients in the workplace,

- Establishment of a dedicated system and prepare a response plan for large-scale absenteeism,

- Sick leave management for confirmed patients and contacts,

- Postponement of special and pre-placement health examinations that may cause splashes during examination, such as pulmonary function examination (pulmonary vitality test, maximum expiratory flow measurement during work, non-specific hypersensitivity test), sputum cell test among workers who have fever or respiratory abnormalities on the examination day.

In addition to the GWR, there was expansion of items relating to occupational safety and health management expenses.

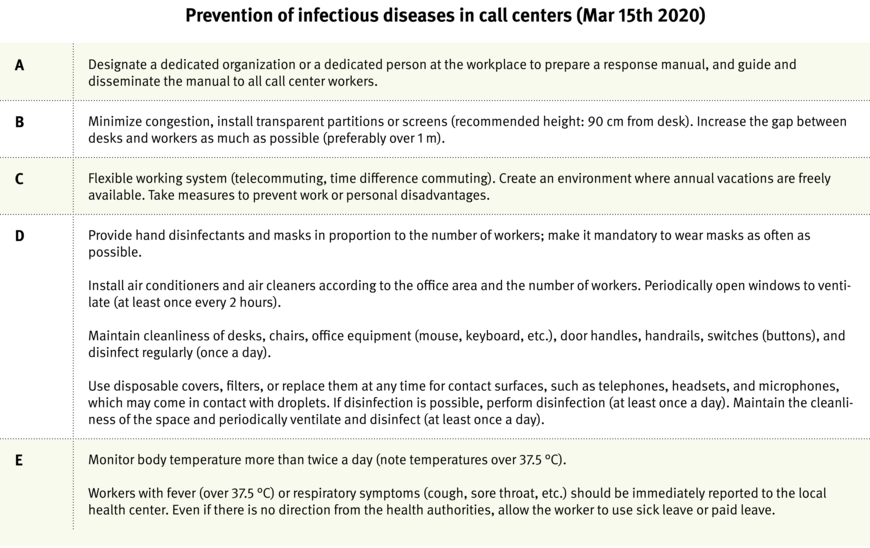

When the alert level was raised to red, CDSCHQ (Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters) and the government-wide network was operationalized. Multi-use facilities and schools were closed. GWR in workplaces was upgraded to strengthen social distancing measures. Considering the outbreaks in call centers, the Ministry of Employment and Labor announced guidelines for call center work (Tabelle 2). The response system in alert level red is presented in Figure 2. Guidelines for call center workers included maintenance of minimum space between workers, screens, flexible working schedules, and detailed instructions for maintaining cleanliness in the workplace (Tabelle 3). In fact, the condensed working space was one of the most important reasons why the attack rate of COVID-19 was so high. Therefore, the guidelines strengthened regulations governing interpersonal space and flexible working schedules in order to minimize congestion in the office.

Distancing in the workplace

There are four[8] components of workplace distancing guidelines: use a flexible working system, minimize meetings and business trips, case monitoring, space management, and disinfection (Table 4). After alert level red, CDSCHQ strongly encouraged flexible working and the use of sick leave. In the majority of private business in Korea, workers do not have enough sick leave. According to IDPA, the employer should provide paid sick leave to workers who need to leave for home quarantine or treatment of infectious disease. The COVID-19 crisis evokes a social discussion regarding provision of paid sick leave to all workers. Another social discussion that started due to COVID-19 was that of presenteeism among workers. Nineteen percent of Korean workers reported presenteeism[9], which could be an important risk factor for contagious disease.

Avoiding face-to-face meetings, business trips, and teaching was another critical component of preventing the spread of workplace infection. Due to an increase in the number of confirmed patients among civil servants, the government implemented three-shift remote work from March 16 as part of the prevention effort. In this non-face-to-face working environment, which was built based on a range of ICT technologies including Cloud Mobile, government officials have been working just as efficiently as if they had showed up at the office. Online educational content can enable students to continue learning at primary, junior high, and high schools[10]. Suspected signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and hygiene procedures were strictly monitored at the gates and front doors of meeting rooms in most public and private workplaces.

To date, meeting the challenges in the workplace due to COVID-19 has not been easy for workers and professionals. As opposed to health care facilities, which are already known to be high-risk workplaces, the risk in call centers and public service offices was unpredictable. The COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, and nobody can predict the outcome. Additionally, there could be another infectious epidemic involving another transformed pathogen that is even more contagious. Therefore, risk assessment in terms of workplace infection continues to be necessary in every workplace. The items in the risk assessment should include flexible schedule, presenteeism, congestion of the workplace, personal density, and the disinfection schedule; the same causes of infection that we observed in the COVID-19 workplace outbreaks. In view of the long term, occupational health should be treated as a more important part of the national crisis response system, so that immediate and consistent policies can be implemented.